Can a Woman Create Her Stake in Society?Somali Women and the Built Environment

The Somali Woman in the Miyyi

Summer in the miyyi. The twisted branches of the Galool tree I lie under offers me very little shade in this climate. Every so often, the low wind stops and an unbearable heat settles on us as the sun inches closer to its peak in the cloudless sky. We have just eaten qado and a sleepy calmness has settled over the household, Hooyo and Habo chatter in low voices, full bellies slowing their speaking to a relaxing tempo. I stretch across the caw, every once in a while shifting in my sleep, arm thrown over my face in frustration. It is the end of July and the village of Faraweyne has settled into the drought season. The absence of rain has made the greenery of the region shrink back, now only the trees and shrubs offer a contrast against the dusty ochre of the dirt ground. I can’t sleep so I watch the Guri from the crook of my arm.

There’s only one solitary figure that dares to stand in the high noon heat. Ayeeyo Fadumo zips from one aqal to another. First she’s in the kitchen cleaning out the Dhiil from yesterday’s milk, then she goes to the Sagara to gather fresh caw to deposit into the cow pen. In between she sweeps the ground, pushing stubborn sand away from the entrances of the Buuls.

Ayeeyo Fadumo is the matriarch of this household. She lives with her son, his young wife and their 2 children: a playful little boy with cheeks like a chipmunk and newborn baby girl. While her daughter-in-law is on bedrest postpartum, she commandeers the many tasks of maintaining the household, from cooking to repairs to the home. In Somali pastoral traditions, the division of labour is based on gender, and both men’s and women’s roles are deemed crucial to the health of the household. However, with roles like shepherding the camels (the most prized possession of the nomadic family), and overseeing the activities and migrationroutes of the family, it is clear the man is still seen as the ‘head’ of the household. Despite this, the presence of Ayeeyo’s son is rarely felt, and it is clear that the authoritative status of the male is enshrined in symbolism alone. In between shepherding the camels, taking them out to graze every morning, and sometimes tilling the fields in the evenings, he is absent, sleeping in in the mornings and passing the hours at a café after waking up at Asar.

Ayeeyo Fadumo’s routine shows us the price women pay to maintain their place in the family dynamic. Although capitalism is commonly associated with a step towards liberation, this is a blind omission of the differences between the sexes and their participation in the labour that is required to accrue capital. In nomadic Somali society, when a herd grows it’s the man’s status that evolves with it, however the woman- who feeds, exercises, and nurtures the cattle alongside him- is not elevated by this same work. She must tend to upkeeping the wealth of males (husband/father) in her family, only ever getting to lay stake to the ‘wealth’ that is her creation; her children and their earnings. However, this is a rudimentary understanding of the role of the woman in society and inaccurate in the case of Somali pastoral culture.

The Somali nomadic family functions as a self-sufficient economic unit, being the site of the first division of labour, which in the case of the ‘Western’ family highlights the first instance of the unequal division of labour, according to Engels. In linking the increase to women’s liberation with an increase in their role in labour production, Engels saw an unexpectedly liberating dimension to capitalism. He even went as far as prioritising the workforce over the nuclear family, understanding that in the conflict between the division of household roles and waged labour, the family unit should be abolished rather than redistributing roles (Dean, 2020). However, rural Somali women offer another angle to Engel’s position: despite demonstrating an equal involvement in every facet of running the pastoral family unit, they are not guaranteed equality or autonomy. This encourages the understanding that there is a difference in women’s relationship with capital and labour: particularly in the distinction between the maintenance of wealth and its acquisition, beyond producing the next generation of workers. I believe the case of rural Somali women introduces the significance of another dimension to this understanding of wealth acquisition through the act of building the Aqal, the built form of the traditional dwelling of Somali nomads. When the woman assumes the role of architect, building the Aqal by hand, she creates her wealth and emboldens her stake in a fluctuous society.

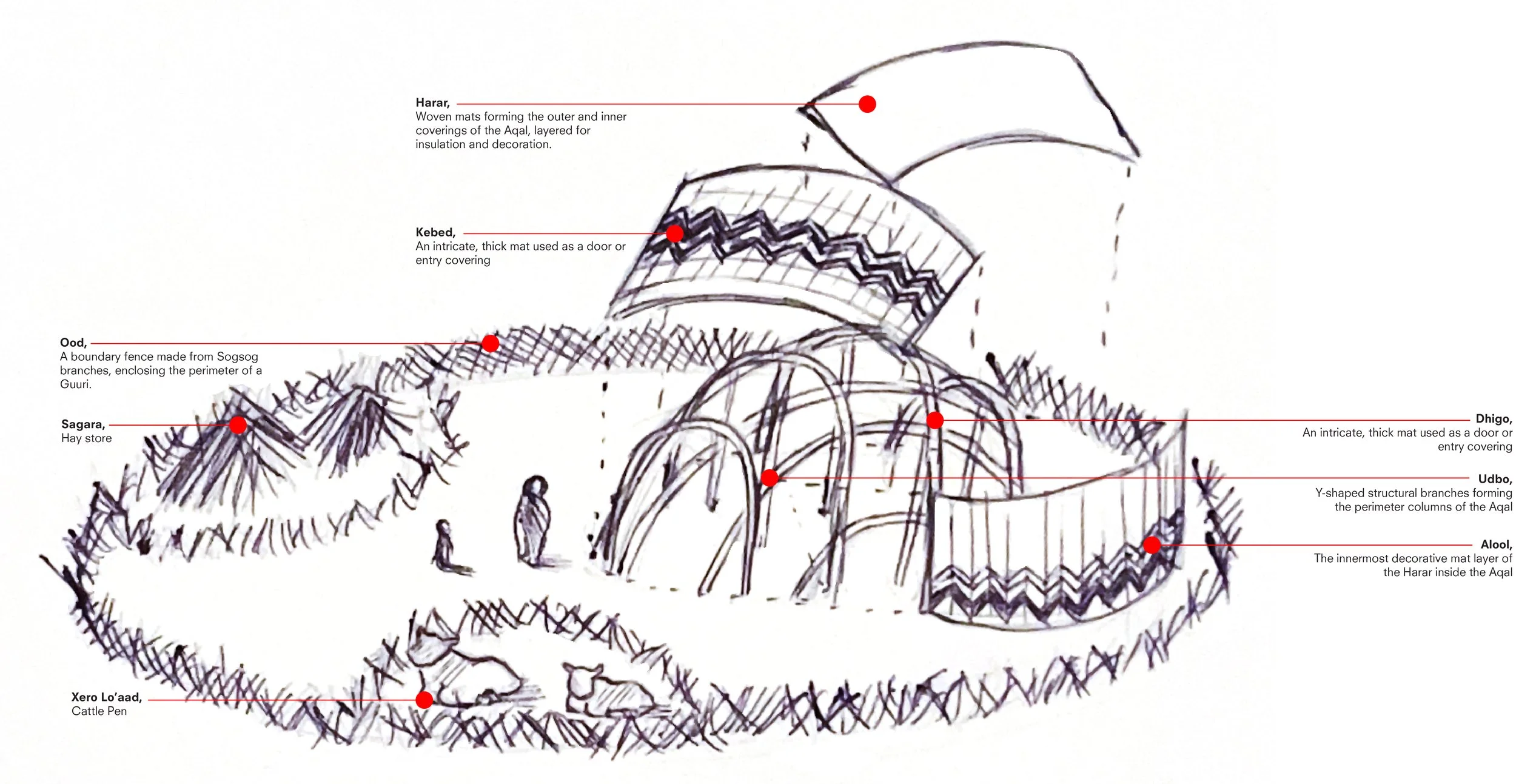

Figure 1 - The Components of the Somali Aqal and Guri

What is the Aqal and How is it Constructed?

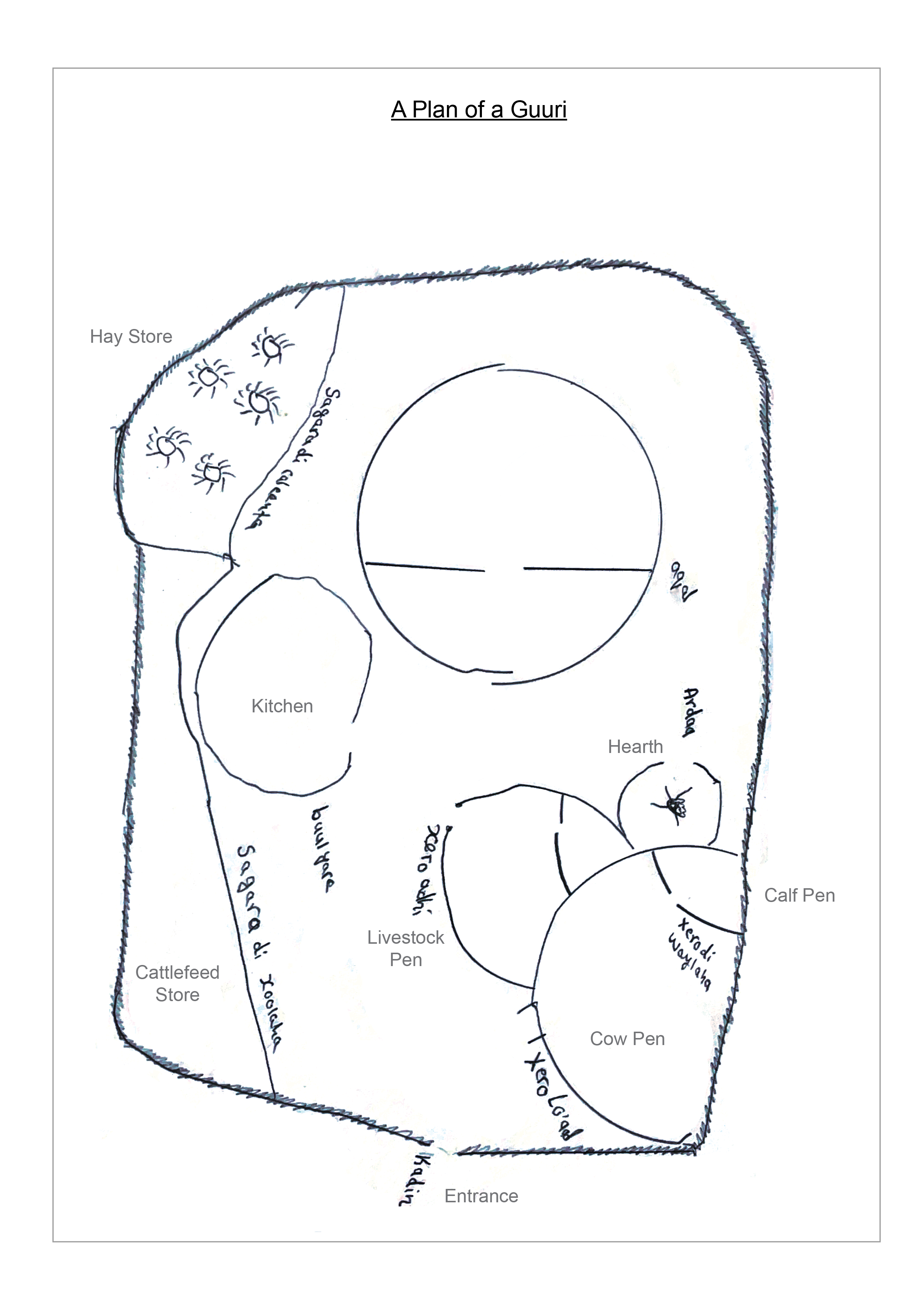

Figure 2 - The Floorplan of the Typical Guuri within the Ood Boundary

Architecture is an instrument of culture, the built environment presents a tapestry of the cultural traditions and taboos of a society. The degree of spatial partitioning is a key aspect to examine: homes with large communal and multi-functional spaces value community and collaboration, whereas homes with singular-functional spaces prefer individuality and privacy. The definition of a ‘home’ is also cultural, some cultures preferring multi-generational living whereas others see homes as the start of a new branch for the singular nuclear family to occupy.

For example, in Saudi Arabia, the importance of privacy combined with the country’s Islamic principles created a unique form of architecture. A typical family home has a somewhat mirrored floor plan, featuring male and female entrances that lead to gender specific reception and dining spaces reflecting the Islamic principles of gender separation in the case of non-related individuals (Abu-Gaueh, 1995). Various kinds of mechanisms, from social and religious preferences to spatial mechanisms like urban density are used to regulate social interaction, therefore the architect must understand these mechanisms precisely to create a useable space. It is through this lens that we can look at the architecture of Somali nomadic dwellings to glean how they corroborateour understandings of gender dynamics. In this context, the fact that the architect of nomadic Somali dwellings is the matriarch of the family is significant. She uses her contextual cultural knowledge to steer social interaction. The matriarch, along with other female family members, creates every aspect of the home from the primary columns that support the skeletal frame to the intricate layers of grass matts that create the building envelope. Several dwellings are created all enclosed in Ood, a thick boundary made of clusters of thorned brambles, to create the homestead or Guri. Therefore the woman can craft not just the physicality of the home, but also its atmosphere, which routes possibly taken and the proximity of the dwellings from one another. Giving the woman a hold over the urban environment seldom seen elsewhere.

Figure 3 - The floorplan of a Saudi Arabian Villa featuring separate living rooms and entrances for men and women

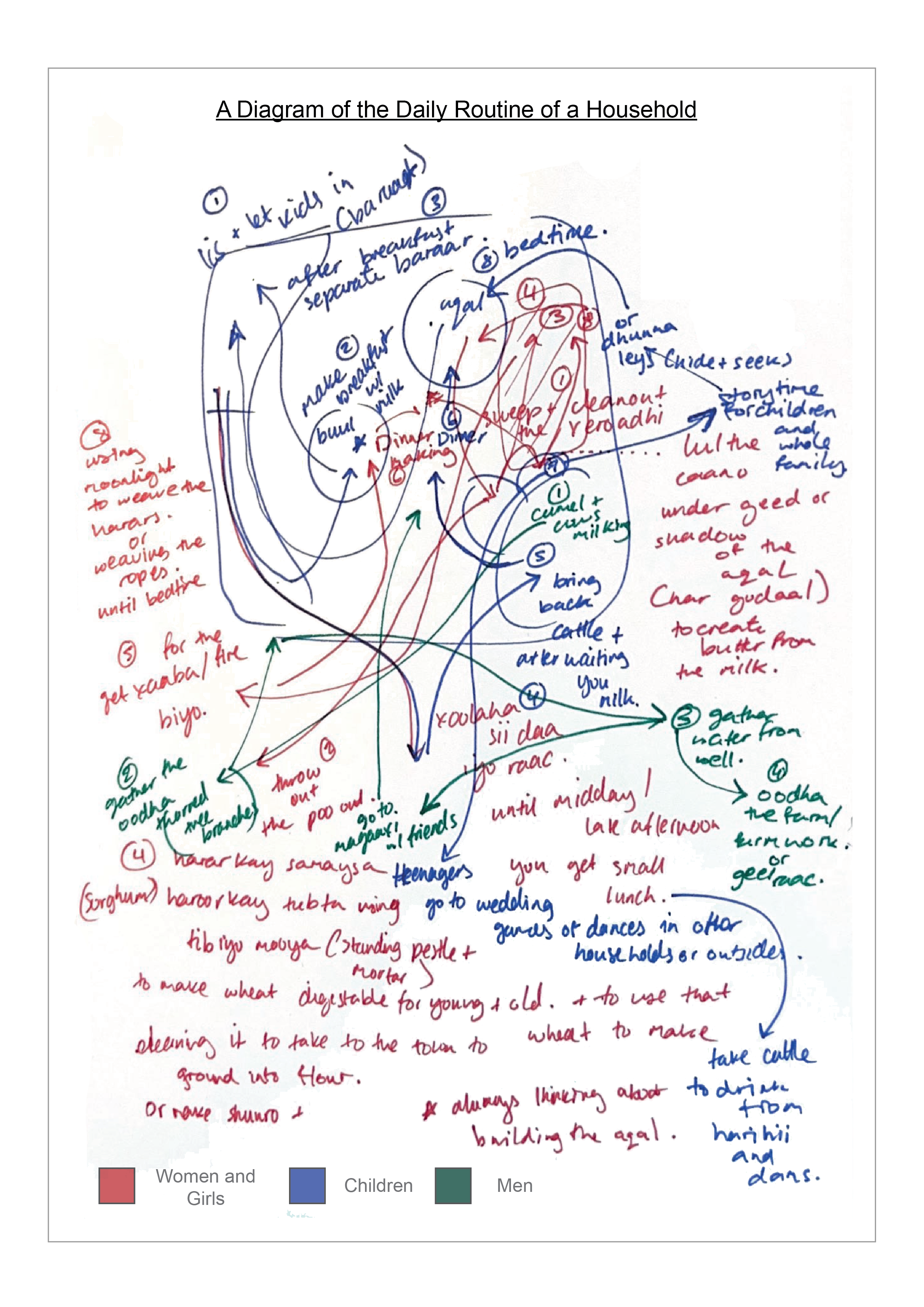

If we understand that the only method to the acquisition of wealth that a woman has is via creation, then we also understand building as a necessary and radical act for survival. Building becomes ‘woman’s work’ but not in the patronising manner prevalent in Western discourse, which relegates ‘women’s crafts’ like weaving and embroidery as lesser than the ‘masculine’ artforms of sculpting and painting, but in a manner that identifies and exalts the woman as the creator of the built form that encompasses all social interactions (Natale, 2023). The dominance of the colour red in the map below reflects how women occupy every single space both within and outside the boundary, whilst men’s tasks exist predominantly on the peripheries of the map.

Figure 4 - The daily routine of the household mapped over a diagram of the Guuri. Produced by Author.

In popular societal discourse the ‘place for the woman’ was always a contentious idea, Victorian gender ideology relegated women to the kitchen and thus architecturally represented this dynamic by designing the kitchen in a narrow gallery at the back of the house. This suggests the continuum of the gender division in space and boundaries, from creativity to use.

The most significant boundary is the Ood, a thick cluster of thorned brambles that define the outer perimeter. Somali nomadic communities fall under 2 umbrellas: Reer Guraa and Reer Qodaal. Reer Guraa describes a nomadic family who move between lands that they do not own, and Reer Qodaal is a semi-nomadic family; they move cyclically between their own farms and other un-owned land. Therefore architectural boundaries must reflect this transient way of life. The Ood is physically porous, but has a distinct spatial permanence, it serves as the architectural distinction between gender roles. The porosity of the Ood means the boundaries fluctuate with every iteration that migration creates, forming not a building footprint but more of a fingerprint. A completely unique imprint tied to the women who built it, asserting that this construction is entirely theirs and in the case of their absence the structure would fall into disrepair and fail. The interior of the Ood, the entire Guri, is unarguably the woman’s space and the exterior is where man’s tasks lie. In the case of nomadic building traditions, men’s primary contributions is the gathering of materials, which frames the tradition of building as a female craft.

Like the endless housework that the woman undertakes, the maintenance of the aqal is also constant. It is architecture as a verb rather than a noun: a communal task that’s carried out, day and night. The life of the nomad is by definition non-static, every aspect is in flux. Their methods of knowledge sharing mirrors this. They boast a proud oral tradition, where technique and method is passed from mother to daughter through song and prose. The aqal becomes something that is not just physically carried on the backs of camels but also in the minds of the Somali women. This has added significance when taken into account the precarious position the woman has in the pastoral family dynamic. Since women cannot head their own household, their role/position under the Xeer (the social contract or governing principles of the nomadic community) is determined by their proximity to men, either a husband or father. In contrast to the elevated status of the men in this society, maintained by their monopoly on production and family, the women maintain a monopoly on this indispensable craft. This is done by keeping the knowledge transfer intangible and cloaked in prose and song.

The Aqal as a Conduit for Female Kinship

If a task is deemed vital to a communities survival, the members of the community who can fulfil the tasks survival is also guaranteed. And in a community where women are spoken for by others, there is a constant danger of their monopoly being encroached upon. By gatekeeping the key to completing this task they are guaranteeing their survival no matter any changes in circumstance.

The Somali language only adopted a written form in 1972 following a government campaign to teach it to all citizens, rural and urban. As a result, poetry became not just a pastime for educated elites but also the language of the common person. Work songs were incredibly popular, and still are to this day; steady mantras giving labourers a momentum to work to. Although the types of poetry are divided along the line of gender, both genders create, compose and sing work songs. Poetry offers an outlet of frustrations for women that might not have a place in day to day society, for example in a culture where polygamy was commonplace and accepted, if not expected, a woman’s protestations would be brushed off. However, in the Salsal, the worksongs of loading the camel, the woman can go unchallenged by her husband (Adan, 1981). She says:

Nabad Gale, nin laba dumar le

Nabad uma soo gelin

For the polygamous my lovely camel

Worry and nagging are his companion

Examining women’s poetry offers a parallel to their role in construction. Foreign writers who visited the Somali peninsula during the colonial period made the mistake of considering women’s poetry forms of Buraanbur (wedding songs) or Hobeeyo (Lullabies) as inferior to the predominantly male Gabay, but women took this in stride and subverted it. In reality these female poetic forms are arguably more entrenched in the daily lives of both rural and urban Somalis. This gender distinction in craft is not oppressive but an act of self preservation. They turned inward and used these poetic forms to speak to each other and their children. In the context of building the aqal, the most symbolic component is the Kebed; It is a colourfully decorated woven mat, which acts as a piece of art hanging over the doorway of the Aqal. Construction becomes a tool for liberation as the community gathers to make a bridal kebed and use the opportunity to reminisce and forewarn, crafting the most interesting worksongs.

Here, between the lines that instruct the listener on how to weave the masterpiece, they speak unflinchingly, not mincing words about the measures to be taken against cruel husbands.

Eddow sidee oday loo galaa

Eddow sidayda loo galaa

Eddow sidaaduna waa sidee

…

Haddu mindiyey ku yadhi

Bilaawe af weyn udhiib

Shantaba hays xaabiye

Haddu barkimo ku yadhi

Aloolba loo ridaa

O aunt, how does one deal with an old husband O

niece, you deal with him the way I do

O aunt will you kindly tell me how?

…

When he asks for knife

Give him a sharpened dagger

(In the hope that) he cuts off his fingers

And if he asks for a mat to sleep on

Throw him the Alool-mat

The kebed songs, despite their shocking contents, are not hidden and whispered, they are sung and chanted out in the open. This affirms that the women have an untested monopoly and it directly links this act of building with a tool to emancipation. They say sit with us, learn from us and we’ll give you the tools to control your future. Control your husband and control your household. The aqal and all its components become a physical manifestation of this invaluable knowledge chain.

Why is the Aqal so important for Somali Women? – the Aqal’s Role in the Nomadic Economy.

This article in its self can be seen as an extension of the female knowledge chain that we have examined. However by noticing how the aqal’s construction is intertwined with womanhood and in turn marriage, it complicates it relationship with capital. By establishing that the aqal is a social and material necessity, its construction is a vital skill.

Marriage is the most important event of the rural woman’s life, it is a key moment of social mobility, not just for her as an individual but for her family. Much of the nomadic economy revolves around the bride price, it is part of an exchange of capital. The prospective husband must bring two gifts: the first is the gabbaati, a sum of money given to the attending members of the bride’s family at the wedding ceremony, the second is the dhabankeeda or yarad, which is the number of camels or cattle gifted by the groom to the bride’s family. In return a bride must bring the dhigo, which is literally her marital home. She brings with her the harar, alool and kebed that she had been labouring over with her friends and family. Beyond the practical, this is when the skill of the woman is put on display, the marital home must speak for her dexterity, craftmanship, wit and character.

A popular Somali saying and song lyric: ‘Geel iyo haweenka waa la hidda raaca’ encapsulates this sentiment perfectly; it means that ‘for both camels and women you must look at their ancestry’. Essentially that as a camel’s pedigree is meticulously examined to determine which good attributes it will obtain, a woman’s background and character must be understood before she is wed into a family. And of this, her skills as a craftswoman are foremost, as the worksong below illustrates, the aqal is living architecture, its constant maintenance with weaving and repairs done under both sunlight and moonlight, means it cannot live without its creator (Xaange, 2014). Thus, the woman’s skills as a craftswoman directly correlate to the symbolic status of her marriage and the health of her family.

Naag aan daah xiraney

Docadalooley

Wan loo diley dugaag gurayey

Tukuhu daanyo-daanyeyey

Ninkeedi dabayl raacyey

Jiiftoo huruddoy

Daah aan jirin jiidoy

Jabtoy jalawdu waa roobey

Kaalin-daraney

Adaan kayd u dii dhigine

She who in her home kebed has not

Her hut hollow-sided remains

Beasts wild would feast on her meat supplies

Crows in and out her hut would fly

Winds cold her man would kill

You, wretched woman

Who kebed that exist not pretends to pull

The rains soon would fall

Drenched and miserable you then be

Conclusion

The life of the rural Somali woman is not an easy one, it is synonymous with hard labour, long hours and a social economic system that sees her as replaceable and interchangeable. However, it is the ties of kinship formed with every fibre of straw woven into the harar and the tightening of the twine that holds the aqal upright that straightens the woman’s back. The aqal is the centre that all aspects of nomadic life orbit, it’s a living entity that’s maintenance facilitates the social interactions necessary for this way of life. It can be the olive branch between warring families or the final act of love of a dying mother. It is the litmus test for understanding the condition of the Somali people. We’ve established that the rules that ordain nomadic life are not written covenants that iron out the intricacies of life but instead a non-verbalised commitment to maintaining social bonds of the wider clan. So far we have viewed the act of aqal-building as a fixed constant throughout time but this raises questions bout how these systems clashed with the rigidity that was implemented by colonial forces in the 19th Century. Safia Aidid (2010) suggests that even though colonialists idealised that their systems would ‘liberate’ the backward desert nomads, Somali women were knocked back several steps and suddenly found themselves on square one; faced with an administration that enforced several barriers to even understanding it let alone interacting with it. For example, marriage was whittled down from being a social institution symbolic of the nomadic principle of ‘reciprocal sharing,’ which allowed nomadic Somali women to function as bearers of social capital to a relationship between two individuals and their immediate families. The next step would be situating this essay in a specific timeframe, there is a huge data gap that bringing it into the modern era allows for a cross-analysis with how urbanisation or global warming has affected these wealth systems. The scarcity of native tree and grass types has meant nomads are turning to more ‘hybrid’ constructions: plastic tarp instead of saan (cattle pelt) for waterproofing or metal sheets around the base of the Aqal for protection against rainwater or poisonous snakes. But as this precious economy is slowly dismantled by urbanisation, how do the women who depended on it fare?

Glossary of Somali Terms

Aqal/Buul – Traditional Somali nomadic dwelling, typically oval-shaped and portable.

Alool – The innermost decorative mat layer of the Harar inside the Aqal, woven from

Dareemo grass and often decorated with strips of fabric for strength and color.

Caw - Grass/hay used for bedding or animal feed also can be fashioned into a floor mat.

Dhabankeeda/Yarad - Bridewealth / bride price—camels or cattle given by the groom’s

family to the bride’s family.

Dhiil – Traditional milk container (often made of gourd or wood)

Dhigo – Long, flexible tree root used to form the curved ribs of the Aqal’s skeleton or the

marital home and furnishings a bride brings

Gabbaati – cash wedding gift to bride’s family

Galool – Type of native acacia tree

Guri – The entire homestead or encampment (including structures and immediate outdoor

activity zone).

Habo – Maternal aunt

Harar – Woven grass panels used in building the Aqal

Hooyo – Mother

Kebed – Decorative woven mat used inside the Aqal

Miyyi – Rural countryside

Ood – Thorn fence enclosure

Qado – Lunch

Reer Qodaal – Semi-nomadic Somali families who move seasonally between their own

farmland and surrounding areas.

Reer Guraa – Fully nomadic Somali families who move cyclically through unowned land,

guided by water and pasture availability.

Saan – Animal hide used for waterproofing

Sagara – Storage hut or space

Xeer – Traditional Somali customary law or governing social contract between clans.

Bibliography

Abu-Gaueh, T. (1995). Privacy as the Basis of Architectural Planning in the Islamic

Culture of Saudi Arabia. Arch. & Comport. / Arch. & Behav, [online] 11(3), pp.269–

288. Available at: https://www.epfl.ch/labs/lasur/wp-

content/uploads/2018/05/ABU-GAZZEH.pdf.

Adan, A.H. (1981). Women and Words. Ufahamu, 10(3).

doi:https://doi.org/10.5070/f7103017286.

Aidid, S. (2010). Haweenku Wa Garab (Women are a Force): Women and the Somali

Nationalist Movement, 1943–1960. Bildhaan : an international journal of Somali studies,

[online] 10, pp.103–124. Available at:

https://catalogue.leidenuniv.nl/discovery/fulldisplay?vid=31UKB_LEU:UBL_V1Cdoci

d=alma9939077065502711Ccontext=L [Accessed 20 Nov. 2025].

Dean, J. (2020). Silvia Federici: The exploitation of women and the development of

capitalism – Liberation School. [online] Liberation School – Revolutionary Marxism for a

new generation of fighters. Available at: https://www.liberationschool.org/silvia-federici-

women-and-capitalism/ [Accessed 5 Nov. 2025].

Natale, M.T. (2023). Women and crafts. [online] Europeana.eu. Available at:

https://www.europeana.eu/en/stories/women-and-crafts.

Xaange, A.C. (2014). Folk SongS From Somalia Axmed CArtAn xAAnge AnnAritA

Puglielli. [online] Available at: https://romatrepress.uniroma3.it/wp-

content/uploads/2019/05/folk-xapu.pdf [Accessed 11 Nov. 2025].